02/15/2007 3:38 PM ET

02/15/2007 3:38 PM EThttp://www.baseballhalloffame.org

By Luis R. Mayoral

Major League Baseball is of great importance in the history of Puerto Rico. It has given the island unforgettable heroes with careers full of great accomplishments, headed by Hall of Famer Roberto Clemente who played for the Pittsburgh Pirates from 1955-1972.

Clemente's days of glory coincided with a period of great social change in the United States. African Americans and Hispanics accelerated their causes for equality and better tomorrows. With resounding pride in his color and heritage, though never to the extent of demeaning others, all Clemente wanted was to make human beings aware of the strengths within themselves.

One Saturday afternoon during the spring of 1972, in his second story spring training room, in Bradenton, Fla., Clemente recalled how proud he was of having met with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Puerto Rico years before. He also discussed how he admired the principles of John F. Kennedy's "Peace Corps Program" to benefit countries around the world.

All countries need heroes, and as a U.S. colony since 1898, Puerto Rico is no exception. During the first half of the 20th century, the country had few internationally known heroes, but Major League Baseball paved the way for Clemente, Orlando Cepeda, Ivan Rodriguez, Juan Gonzalez, Bernie Williams and so many others.

To Puerto Ricans, the national flag and Clemente are common denominators. He leads a very select group of islanders, who by way of sports, arts, sociology, science and politics, touch millions around the world in attempts to contribute to the greatness of man.

On Dec. 31, 1972, while on a goodwill mission to aid earthquake victims in Nicaragua, Clemente, 38, died when his plane crashed a few miles northeast of Puerto Rico's main airport. Today, I still recall the words of Elfren R. Bernier, a former president of the Puerto Rican Bar Association: "Puerto Rico has always been a country divided by religious, political and social matters, but Puerto Rico was always united in admiring and respecting Roberto."

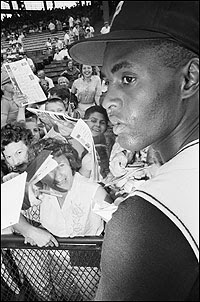

Clemente, left, with Willie Mays and Henry Aaron at the 1961 All-Star Game.

Clemente, left, with Willie Mays and Henry Aaron at the 1961 All-Star Game.Years after his death, Clemente's friend, Bill Guilfoile, who spent nearly 40 years in public relations with the Yankees, Pirates and the Baseball Hall of Fame, wrote, "Here in the Hall of Fame, I think a lot and, you know, Roberto died with the same dignity with which he played the game. No head of a mission of mercy, like Roberto in relation to Nicaragua, travels on December 31, to encounter death. Most leaders would send others, but not Roberto."

Imperfectly human, as we all are, Clemente reached martyrdom not only for his triumphs on the playing field, but with simple deeds and thoughts. Maintaining a strong work ethic, helping others whenever possible, and keeping alive the family concept were several of his personal campaigns.

I think about Clemente frequently. His smile had something peculiar. It was difficult to decipher. If I spoke a truth about him that he did not want to admit, he would come back with that smile. He told me several times that he was so strong, that at six years of age, he could take a nail and bend it with his hands. Then he would offer that smile.

Sharing time with Clemente was fun. We hardly talked baseball. Most of the time, we would philosophize about life. He loved to tell stories.

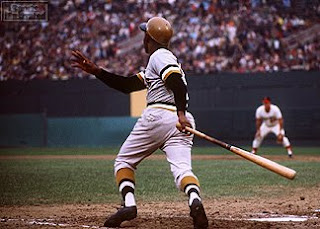

Pirates outfielder Roberto Clemente hits against the Orioles during the 1971 World Series at Memorial Stadium in Baltimore.

Pirates outfielder Roberto Clemente hits against the Orioles during the 1971 World Series at Memorial Stadium in Baltimore."Once in San Francisco," he said, "I hit a great shot to right-center field that appeared to be a sure home run, but the wind held the ball and Willie Mays caught it. I got so mad that I threw my helmet up in the air and the wind blew it right out of the park." He paused and said, "Ask Orlando Cepeda, he was there." Then he gave me that smile of his.

During the winter of 1970-1971, in the balcony of his home overlooking San Juan, he told me, "Late one night, an old lady knocked at the door. She was all bent over in pain and told me that God had sent her to me so that I could treat her with my massages." With a sense of great satisfaction, he added, "I gave her such a 'pop' of the back and a 'crack' of the neck and she walked away just fine."

Helping that woman was a highlight to him.

His large hands come to mind - to me they reflected his spirit. He would grip the bat with the strength of a tiger, but those same hands became extremely gentle when he saw a child and patted his or her head. With those talented hands, he made ceramic objects. He never studied music, but he played the organ quite well Let us not forget that at the time of his death, he was caring for people by means of chiropractic methods.

In Major League Baseball, in Puerto Rico and in the Hispanic culture of the game, Roberto Clemente equals number 21 and vice versa. The right field wall at PNC Park in Pittsburgh is 21 feet high, in honor of the great Pirate.

In Major League Baseball, in Puerto Rico and in the Hispanic culture of the game, Roberto Clemente equals number 21 and vice versa. The right field wall at PNC Park in Pittsburgh is 21 feet high, in honor of the great Pirate.Number 21 has a history of its own. Several nights after Clemente's plane crashed, I sat down with his dear friend, Phil Dorsey, in San Juan. Dorsey, now in his 80s, met Clemente in the spring of 1955 through pitcher Bob Friend. Dorsey was Friend's sergeant in the Army Reserve. Knowing that Clemente would need help in adapting to life in the USA, Friend asked Dorsey, an African-American postal employee, to assist the young player.

Dorsey recalled, "During the 1955 season, Roberto and I would go to the movies. One night before the show began he wrote his full name - Roberto Clemente Walker - on a piece of paper." Clemente then turned to Dorsey and said, "My full name is made up of 21 letters. I'm going to see if the Pirates will give me that number."

On the night of Sept. 30, 1972, hours after reaching his 3000th hit, in a room in his Greentree, Pa. apartment, he told Dorsey and me after reflecting on his accomplishments, "Now, at last, they know me for the player that I am."

He did not use other adjectives to describe his abilities. He simply said, "The player that I am."

He did not use other adjectives to describe his abilities. He simply said, "The player that I am."The recent World Baseball Classic, of which Puerto Rico was one of the hosts, brought Clemente to my mind repeatedly. Seeing so many fans enjoying major league caliber baseball in my country made me think of his legacy.

For Clemente, the Classic would have been a dream come true, a dream he shared with his longtime friend, Bob Leith, a successful San Juan businessman.

Joe L. Brown, the Pirates general manager during Clemente's 18-year career, once said of him, "You could never capture the magnificence of the man."

Former MLB Commissioner Bowie K. Kuhn stated at the time of his death, "He had about him a touch of royalty."

In Puerto Rico, we remember Roberto Clemente as a national hero, an outstanding humanitarian, an inspiration for the needy as well as a man who was able to solve the human, social and political challenges that life presented to him.

He gave Puerto Rico a sense of identity, new concepts as to hope and respect, and above all, his biggest legacy is that he is still an inspiration 33 years after his death.

A native of Puerto Rico, Luis R. Mayoral spent nine years as a Texas Rangers and Detroit Tigers official and is in his 37th year in baseball. An author of five baseball books, he coordinated MLB's Latin American Baseball Players' Days for 25 years. He has been honored by the Puerto Rican, Mexican and Laredo-Texas Halls of Fame. A veteran of over 2,000 MLB radio broadcasts, he was a guest speaker at Harvard University in 1992 and a guest of President George W. Bush at the White House in 2001. Hall of Famers Roberto Clemente and Orlando Cepeda have been his inspirations and mentors.

A native of Puerto Rico, Luis R. Mayoral spent nine years as a Texas Rangers and Detroit Tigers official and is in his 37th year in baseball. An author of five baseball books, he coordinated MLB's Latin American Baseball Players' Days for 25 years. He has been honored by the Puerto Rican, Mexican and Laredo-Texas Halls of Fame. A veteran of over 2,000 MLB radio broadcasts, he was a guest speaker at Harvard University in 1992 and a guest of President George W. Bush at the White House in 2001. Hall of Famers Roberto Clemente and Orlando Cepeda have been his inspirations and mentors.

No comments:

Post a Comment