Mario the player eventually became Mario the human

Mario the player eventually became Mario the humanPosted: Tuesday January 24, 2006 2:06PM;

Updated: Tuesday January 24, 2006 8:12P

Sports Illustrated

More health problems finally forced Mario to call it quits again.

RELATED

• MUIR: Pens are now firmly Crosby's team

• GALLERY: Scrapbook of Mario's career

• Reactions to Mario Lemieux's retirement

To hell with F. Scott Fitzgerald. There are second acts in America (and Canada), acts even better than the first one, as in the case of Mario Lemieux.

There also are, sadly, second retirements.

On Tuesday, Lemieux said goodbye to hockey a second time, this time more of a proper farewell than he afforded the game -- or the game afforded him -- the first time. The Pittsburgh Penguins center orginally left after a 1997 playoff loss in Philadelphia, escaping faster than the Barrow Gang after a bank heist. He didn't walk away from the NHL, he sprinted.

After battling Hodgkin's Disease and chronic back problems, his hockey immune system rejected the "garage league" he thought he was leaving behind forever, the on-ice rodeo in which players with his glorious skill were not allowed to exhibit it. Almost since the day he entered the league as a pimply 18-year old, there were damning whispers Lemieux didn't have much passion for the game. What originated as a smear, based largely on his languid style on the ice and his diffidence off it, ultimately became an apt description.

If Lemieux didn't love the game by that point, it shouldn't have been startling that the game really didn't love him back. Outside of Pittsburgh, no one seemed to notice, or care, that he had retired. This was not a long goodbye, but a quick good riddance to a player who inarguably was among the 10 best in history. Gone in 60 seconds, forgotten in 60 minutes.

Maybe the gaps in his résumé, a product of his injury and illness, had given the hockey world enough of a glimpse of life post-Mario that when he did bolt almost nine years ago, it did not seem to be the major loss his retirement seems now.

The reason: In his way, Mario II was more impressive than Mario I.

This notion seems so counter-intuitive. Mario II was never a sure bet to be in the lineup, let alone on the scoresheet. Mario I was flat phenomenal. He had only one peer, Wayne Gretzky, during much of his first act, and you could have a splendid barstool argument over which was better in his prime.

Like Gretzky, Lemieux recorded Nintendo numbers. Like Gretzky, he became the foundation of a Stanley Cup-winning franchise, although it took him seven years to win his first Cup; Gretzky needed five. Lemieux once scored five goals in a game five different ways: even-strength, power play, short-handed, penalty shot and empty net, proof that the man who scored on his first shot on his first NHL shift really could do it all. With his reach and vision and underrated hockey IQ, he turned plumbers into 40-goal scorers (Warren Young) and made good Penguins teams into champions.

Of course the Lemieux who returned after a 3½-year hiatus was not the same player. More important, he was not the same person. His first game back, in late December 2000, at Mellon Arena, was an emotionally dappled triumph as his retired No. 66 came down from the rafters. But the spotlights that night felt more like soft backlights that cast a flattering glow on Lemieux, something that had escaped him even during his 199-point season of 1988-89 or the pair of Cup runs in 1991 and 1992.

He had shrunk some as a player, grown mightily as a man. He seemed more human somehow, at peace with his changing skills and himself.

There was an economic imperative for his returning to the ice -- the bankrupt franchise owed him millions and the Penguins were worth more with him as a leader than a creditor -- but his desire to impress his young son, Austin, who had no recollection of his father as a player, seemed as genuine as it was charming. Lemieux had more time now, time for the game he had missed and time for the people around it. He viscerally enjoyed hockey now, and fans began to enjoy him more than they did a decade earlier.

Lemieux had 35 goals and 76 points in 43 games during that wondrous half season, a 1.77 points-per-game average that exceeded scoring leader and teammate Jaromir Jagr by more than a quarter of a point. The question: Was Mario that good or was the rest of the league that ordinary?

In 2000-01, Lemieux had not returned for a victory lap. He had returned for some victories.

No longer the dazzling scorer who terrorized goalies, he was more of a conduit. Lemieux did not control the play, but it almost always came through him. Literally. In Salt Lake City, he opened his legs, like making a dummy in soccer, and let a puck slide through to a teammate in the offensive zone for an easy goal.

Lemieux would be captain of the first Canadian team in 50 years to win Olympic gold, even though he would play in just 24 games that season because of a hip injury sustained in early October. If Pittsburgh resented his scratching an Olympic jones at the expense of the Penguins, he has long since been forgiven.

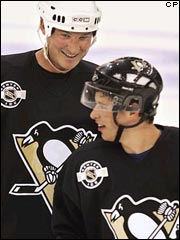

With Lemieux, there was always something. Cancer. Back. Hip. Now heart. The atrial fibrillation flared during the summer, but his appetite for the game wouldn't allow him to shut it down until Dec. 16, when his condition deteriorated and he had no choice. The Penguins had won the lottery -- the rights to Sidney Crosby -- and he was not about to disappear again without at least trying out some of the winnings.

Other than perhaps Rocket Richard and Montreal, no player in hockey history is so intimately linked with one city, one franchise. Lemieux saved the Penguins in 1984 as a rookie, won them championships as a veteran, and saved them again as an owner. He has put them up for sale as the eternal new arena-watch continues, intent on selling to someone who plans to keep the team in Pittsburgh.

Of course, there are no guarantees. As Lemieux knows better than anyone, sometimes life gets in the way. Those slam-dunk free agents of the summer -- Sergei Gonchar, Ziggy Palffy, Jocelyn Thibault -- haven't worked out. New coach Michel Therien has savaged his players, and the Penguins have devolved into a dysfunctional mess.

Maybe Mario III can figure it out before the team implodes or moves, but he will have a tough act, Mario II, to follow.

Find this article at: http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/2006/writers/michael_farber/01/24/mario/index.html

No comments:

Post a Comment